Modern life is optimized for replacement. Objects, ideas, careers, relationships, even identities are designed to be exchanged, refreshed, or abandoned with minimal friction. This is not an accidental outcome of technological progress; it is a structural feature of the world we have built. Turnover is no longer a side effect of growth — it is the growth model itself.

Yet permanence has not disappeared. It has merely become rarer, harder to recognize, and more costly to defend.

This essay is about that tension: why permanence matters, why it has become unfashionable, and why certain forms of value can only exist when turnover slows down — or stops entirely.

The Architecture of Turnover

Turnover once described a measurable event: inventory rotation, labor replacement, asset cycling. Today it has become a worldview.

In markets, faster turnover is often interpreted as efficiency. In culture, novelty is confused with relevance. In personal life, optionality is framed as freedom. The underlying assumption is consistent across domains: what can be replaced easily must not matter very much.

This assumption is deeply mistaken.

Turnover is not neutral. It shapes incentives, behaviors, and ultimately perception itself. When systems are designed to cycle rapidly, they discourage depth. Anything that requires time to mature becomes economically awkward. Anything that demands patience is labeled inefficient. Anything that resists substitution is seen as fragile or obsolete.

The result is a civilization structurally hostile to long formation processes — whether those involve skills, trust, reputation, or meaning.

Permanence Is Not Stasis

One common misunderstanding is to equate permanence with immobility. In reality, permanence is dynamic. It does not imply that something never changes; it implies that change occurs within a stable identity.

A language evolves over centuries, yet remains recognizably itself. A legal tradition absorbs reforms without losing continuity. A craft adapts tools while preserving standards. A person matures without becoming someone else entirely.

Permanence is not the absence of change; it is resistance to disposability.

What distinguishes permanent structures from transient ones is not rigidity but memory. Permanent things remember where they came from. They carry accumulated context forward rather than discarding it.

The Market’s Uneasy Relationship with Time

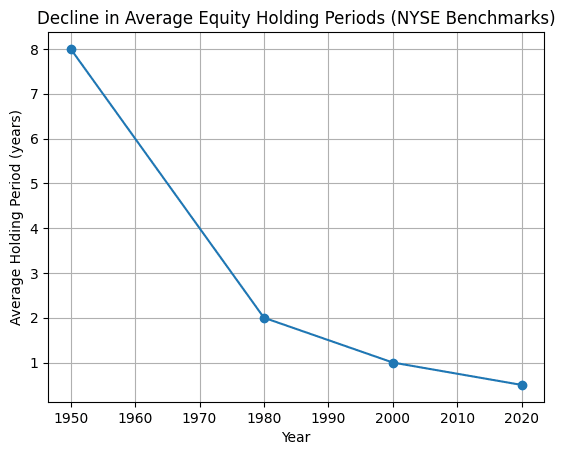

Financial markets are especially conflicted about permanence. On the surface, markets reward long-term thinking. In practice, they increasingly incentivize speed.

Trading volumes have exploded while average holding periods have collapsed. Corporate strategies are evaluated quarter by quarter. Products are designed for rapid obsolescence not because consumers demand it, but because balance sheets do.

This has consequences.

When turnover accelerates, price becomes louder than value. Signals dominate substance. Liquidity is mistaken for resilience. The ability to exit replaces the willingness to commit.

Figure 1: Average equity holding periods have collapsed over the last seventy years, reflecting a structural acceleration of market turnover. Figures shown are widely cited NYSE-era benchmarks.

The irony is that markets depend on trust, yet trust is one of the few assets that cannot be accelerated. It accumulates slowly and collapses quickly. High-turnover environments systematically underinvest in it.

Why Permanence Feels Uncomfortable Today

Permanence introduces asymmetry. Once you commit to something that cannot be easily reversed, your future becomes constrained. Modern culture treats constraints as threats.

Optionality — the ability to change direction without consequence — has become the dominant virtue. Yet optionality without commitment produces shallow outcomes. A life composed entirely of exits rarely arrives anywhere.

The discomfort with permanence is also psychological. Permanence forces confrontation with limits: of time, of attention, of choice. It reminds us that not everything can be optimized simultaneously. Some things must be chosen at the expense of others.

Turnover, by contrast, postpones reckoning. It offers the illusion that nothing is final — until it is.

Enduring Value Is Often Invisible Early

One reason permanent value is undervalued is that it does not announce itself loudly at inception. Many of the most enduring institutions, ideas, and assets began as marginal, unfashionable, or misunderstood.

Endurance reveals itself only through time. That makes it difficult to price in advance.

Markets excel at discounting the future, but permanence often requires ignoring short-term feedback. This creates a selection bias: systems reward what looks successful quickly, not what remains meaningful later.

As a result, durable value often survives despite markets, not because of them.

Cultural Turnover and the Loss of Accumulation

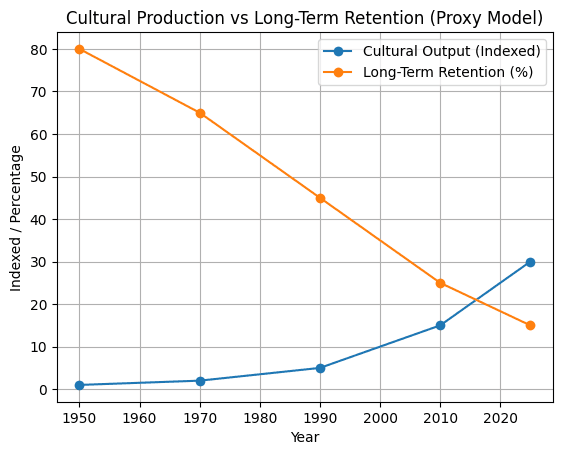

Culture suffers particularly under high turnover conditions. When creative output is judged primarily by immediate engagement, depth becomes optional.

Works that require rereading, revisiting, or maturation struggle to survive in environments optimized for instant consumption. Algorithms reward velocity, not resonance.

This does not mean great work no longer exists. It means it is harder to detect amid noise.

Figure 2: While cultural production has expanded exponentially, the share of works that retain long-term relevance has declined sharply. Retention figures are proxy-based, reflecting long-term citation, reprinting, and back-catalog consumption.

Permanent cultural artifacts share a trait markets dislike: they refuse to peak quickly. They settle slowly into consciousness, sometimes over generations.

Institutions and the Fear of Commitment

Institutions mirror the culture that creates them. When permanence is devalued socially, institutions become risk-averse in paradoxical ways.

They avoid long commitments while entrenching short-term procedures. They rotate personnel rapidly while preserving bureaucratic inertia. They change surface language frequently while resisting substantive reform.

The result is institutional fragility disguised as flexibility.

Institutions built for turnover struggle to defend principles because principles, by definition, restrict optionality. It becomes easier to manage processes than to uphold standards.

Personal Permanence in an Age of Replacement

At the individual level, turnover manifests as serial reinvention. Careers are reframed repeatedly. Identities become modular. Relationships are evaluated for utility rather than continuity.

While adaptability is necessary, constant reinvention has costs. It fragments narrative coherence. It erodes trust — both self-trust and social trust. It replaces character with performance.

A person anchored in nothing permanent becomes endlessly adjustable — and therefore replaceable.

This is not an argument against change. It is an argument against unbounded reversibility. Some decisions should be difficult to undo. That difficulty gives them weight.

Permanence as a Moral Concept

Permanence is not merely economic or cultural; it is moral.

To commit is to accept responsibility over time. To build something meant to last is to acknowledge future stakeholders. To preserve memory is to resist erasure.

Turnover cultures subtly reframe responsibility as inconvenience. They prefer systems where consequences can be externalized, deferred, or reset.

Permanent structures resist this. They make responsibility unavoidable.

What Actually Endures

Across domains, enduring entities share certain properties:

They accumulate meaning rather than exhaust it.

They improve through use rather than degrade.

They are harder to replace than to maintain.

They require stewardship rather than optimization.

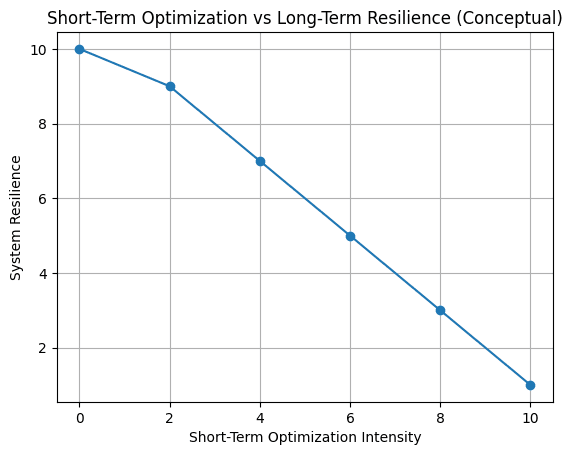

These traits are increasingly rare not because they are obsolete, but because they are incompatible with high-turnover systems.

Figure 3: Conceptual relationship between short-term optimization and long-term resilience. As systems prioritize efficiency and reversibility, resilience declines.

Why Permanence Still Matters

Despite everything, permanence continues to exert gravitational pull.

People still seek institutions they can trust.

They still value work that outlasts trends.

They still remember what shaped them long after novelty fades.

The hunger for permanence does not disappear when systems ignore it. It simply goes unmet — or finds expression elsewhere.

Choosing Permanence Is a Countercultural Act

To choose permanence today is to accept friction. It means moving slower than systems expect. It means tolerating periods of invisibility. It means resisting metrics designed for turnover.

But it also means building something that can be inhabited, not merely consumed.

Permanence cannot be scaled easily. It cannot be rushed. It cannot be faked indefinitely.

That is precisely why it matters.

Closing Reflection

A world built for turnover does not abolish permanence. It obscures it. It pushes it to the margins, where it waits quietly for those willing to notice.

Markets may reward speed. Culture may celebrate novelty. Institutions may prefer reversibility.

Time, however, remains indifferent.

And time has always been the final judge of what endures.