Introduction: The National Passports of the Internet

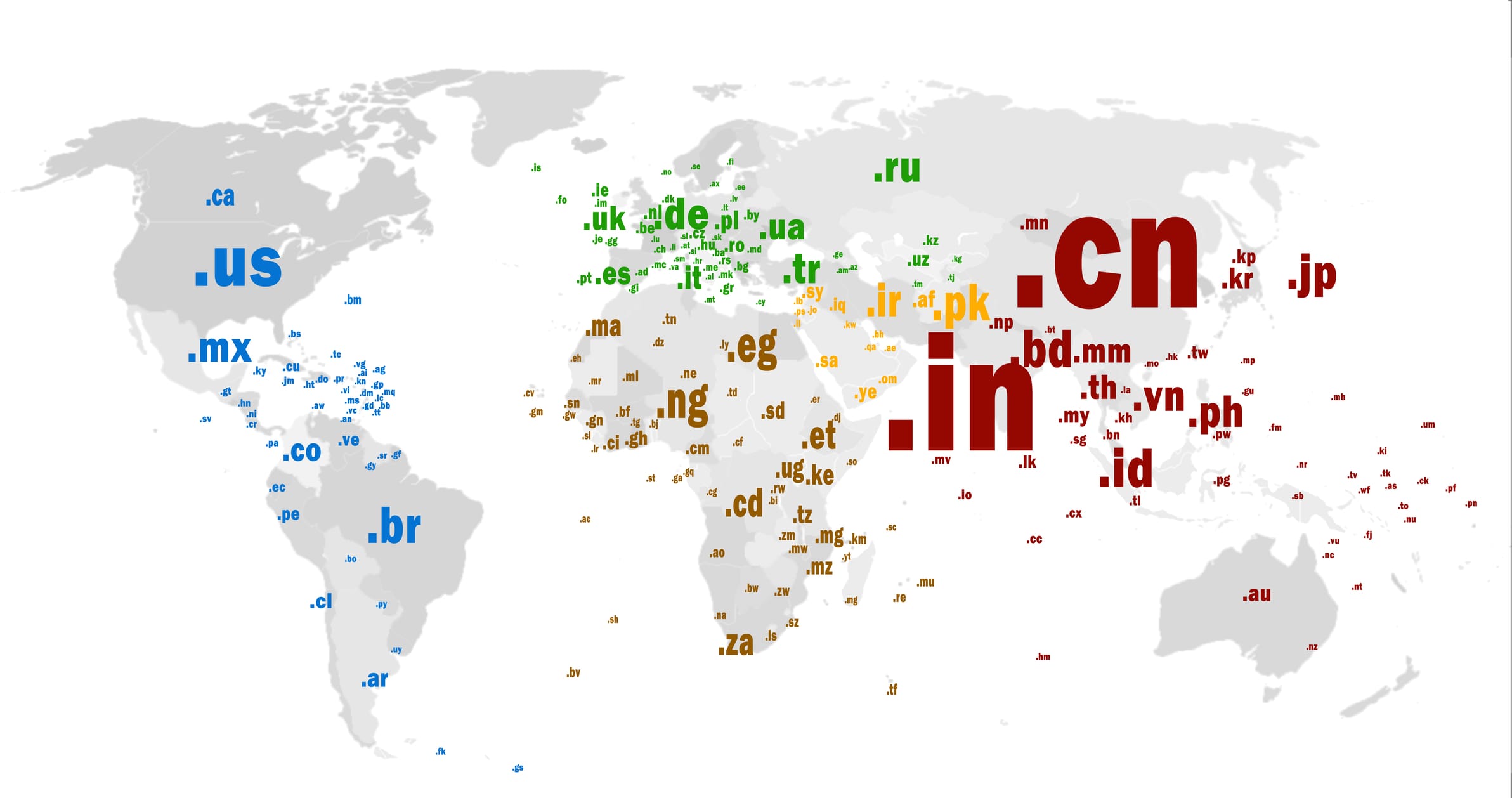

Every domain name ends with an extension: .com, .org, .net, and thousands more. But among them, one family carries a unique weight—country code top-level domains, or ccTLDs. These are the two-letter digital markers assigned to nations and territories: .de for Germany, .ca for Canada, .uk for the United Kingdom, .cn for China, .in for India.

At first glance, ccTLDs look like bureaucratic artifacts, derived directly from ISO-3166 country codes. But in practice, they became much more: symbols of sovereignty in cyberspace, gateways to local trust, and eventually, powerful strategic branding tools far beyond their borders.

This article traces the past, present, and likely future of ccTLDs—how they evolved from national identity badges into multi-billion-dollar digital assets, and why their importance in the secondary domain market is poised to grow.

The Early Years: Sovereignty in Cyberspace (1980s–1990s)

The domain name system (DNS) was born in the early 1980s, replacing unwieldy numeric IP addresses with human-readable names. In 1985, the first top-level domains (TLDs) appeared: .com, .net, .org, .gov, .edu, and .mil.

But the architects of the internet recognized that nations, too, needed representation. So in 1985 the first country code domains were delegated. The format was simple: two-letter codes drawn from the ISO-3166 standard.

- .us was assigned to the United States in 1985.

- .uk was delegated to the United Kingdom that same year.

- .de followed in 1986 for Germany, quickly gaining traction as West Germany modernized its infrastructure.

- .ca was delegated in 1987 to represent Canada.

At this stage, ccTLDs were not commercial assets. They were mostly administered by universities, non-profits, or national research institutes, often with little thought to future value. For example, .de was originally managed by the University of Dortmund; .uk by Nominet UK.

The key principle was sovereignty. Just as nations issue passports, ccTLDs were the digital passports of states. Owning a .fr domain signaled “this is French”; owning a .jp domain meant “this is Japanese.”

The Commercial Turn: From Academic Roots to Market Assets (1990s–2000s)

The 1990s brought the dot-com boom and with it, a surge in domain registrations. Businesses realized that owning the right name could mean owning an entire category online. Yet as .com heated up, many ccTLDs began to emerge as alternatives.

Local Trust

European businesses in particular were quick to adopt their ccTLDs. In Germany, .de became the default choice for companies and consumers, overtaking .com in popularity. By the late 1990s, .de registrations numbered in the millions. Today it remains the largest ccTLD globally.

In the UK, .co.uk became standard for commercial entities, backed by Nominet’s careful stewardship. Similarly, .nl (Netherlands) and .fr (France) entrenched themselves as trusted local identities.

The U.S. Exception

Ironically, the .us extension languished in obscurity for decades. American businesses overwhelmingly preferred .com, which quickly became the global gold standard. It was only after 2002, when Neustar relaunched .us for general public registration, that it saw modest growth.

Regulation and Sovereignty

Some countries imposed strict rules:

- Canada required proof of residency or incorporation to register .ca.

- France limited .fr to entities with a French presence.

- China heavily restricted .cn, with registrations tied to government approval.

These policies reinforced the sovereign identity of ccTLDs but also slowed global adoption.

The Creative Reuse Era: ccTLDs as Global Brands (2000s–2010s)

In the 2000s, something unexpected happened: small nations with little internet infrastructure discovered their ccTLDs could become global brand assets.

Examples of Reinvention

- .tv (Tuvalu): With its lucky coincidence of matching “television,” Tuvalu’s ccTLD became the go-to for media companies and streaming services. Licensing deals turned .tv into a national revenue source.

- .me (Montenegro): Marketed for personal branding (“about me,” “hire me”), .me attracted individuals and startups worldwide.

- .co (Colombia): Positioned as a shorter, sleeker alternative to .com, .co found traction among startups, especially in Silicon Valley.

- .io (British Indian Ocean Territory): Despite its geopolitical controversy, .io was adopted en masse by tech startups, thanks to its association with “input/output.”

- .ai (Anguilla): A quiet island domain that exploded once “AI” became shorthand for artificial intelligence. By the late 2010s, .ai sales were rivaling mid-tier .com names.

The Business of ccTLDs

For some nations, ccTLD licensing fees became significant revenue streams. Tuvalu, one of the smallest countries in the world, reportedly earned millions annually from .tv. Anguilla’s government now benefits from a boom in .ai registrations and aftermarket sales.

Shift in Perception

By the 2010s, ccTLDs were no longer just about local sovereignty. They had become strategic assets for global industries, sometimes completely detached from their geographic origins.

The Present: ccTLDs as Parallel Pillars of the Domain Market (2020s)

Today, ccTLDs are indispensable pillars of the domain name ecosystem. They serve two overlapping but distinct roles:

1. National Trust Anchors

- Europe: ccTLDs dominate. In Germany, .de domains outnumber .com in use by businesses and individuals. Dutch consumers overwhelmingly prefer .nl.

- Asia: Adoption varies. China’s .cn is large but tightly controlled. Japan’s .jp and India’s .in have moderate adoption.

- Canada & Australia: .ca and .au signal authenticity and local presence.

2. Global Branding Shortcuts

- .ai = artificial intelligence startups.

- .io = tech/software ventures.

- .co = global startups.

- .tv = media and streaming.

These dual roles mean ccTLDs now account for over 40% of the world’s domain registrations. They are not secondary to .com, but parallel pillars of the system.

Current Market Data: ccTLD Registrations and Market Share

To ground this in numbers, here’s a snapshot of the ccTLD landscape (approximate figures as of 2024):

| Extension | Registrations (millions) | Notable Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| .de | 17+ | German market dominance |

| .cn | 20+ (fluctuates) | Massive Chinese presence, government controlled |

| .uk | 10+ | UK business and institutions |

| .nl | 6+ | Preferred in Netherlands |

| .fr | 4+ | French market |

| .ru | 5+ | Russian market |

| .ca | 3+ | Canadian trust anchor |

| .au | 4+ | Australian businesses |

| .eu | 4+ | Pan-European identity |

| .ai | <1 (but growing fast) | Artificial intelligence startups |

| .io | ~1 | Tech/startup scene |

Importance in the Secondary Market

ccTLDs also generate significant aftermarket sales. Examples include:

- AI-related sales: voice.ai ($105,000), music.ai ($101,500), expert.ai ($95,000).

- German market sales: auto.de and versicherung.de (insurance) have sold for six figures.

- .co sales: o.co famously sold to Overstock for $350,000 (though later abandoned).

- .me sales: fb.me (Facebook’s URL shortener) was a high-profile acquisition.

For investors, ccTLDs are no longer niche curiosities—they are liquid assets with proven six- and seven-figure potential.

Risks and Challenges

ccTLDs also carry unique risks:

- Regulatory Uncertainty: Governments may tighten rules, as China has with .cn. Some ccTLDs could be revoked or repurposed.

- Geopolitical Tension: The fate of .io is complicated by the contested sovereignty of the Chagos Islands.

- Market Saturation: Some rebranded ccTLDs may lose steam if the hype fades.

Despite these risks, ccTLDs have proven remarkably resilient, often adapting to new cycles of global demand.

The Likely Future (2025–2035)

Looking ahead, several trends are clear:

1. Local Sovereignty Will Strengthen

Governments increasingly see ccTLDs as strategic national assets. Expect stricter residency requirements, enhanced cybersecurity, and perhaps even integration with digital ID systems.

2. Global Niches Will Deepen

- .ai is likely to remain the flagship of the artificial intelligence sector.

- .io may lose momentum if sovereignty disputes intensify, but its tech identity remains strong.

- Other small-nation ccTLDs may attempt similar branding (e.g., .gg for gaming).

3. ccTLDs vs. New gTLDs

Many new gTLDs (like .xyz, .app, .shop) compete for attention. But ccTLDs enjoy an advantage: they are baked into the very structure of the internet, tied to nations. That gives them both credibility and permanence.

4. Consolidation of Value

We’ll likely see a bifurcation:

- Nationally dominant ccTLDs (de, .fr, .nl, .ca) will remain trust anchors in their markets.

- Globalized ccTLDs (ai, .io, .co, .tv) will continue commanding premium aftermarket sales.

5. New Forms of Digital Sovereignty

In the long term, ccTLDs may become tools in digital geopolitics. Control of a ccTLD registry could be as strategically valuable as control of a port or an oil pipeline. Nations will not treat them lightly.

Conclusion: From Sovereignty to Strategy

ccTLDs began as symbols of sovereignty, little more than digital passports for nations. Over four decades, they evolved into strategic branding platforms, serving both local trust and global industries.

Today, ccTLDs represent:

- Sovereignty → the digital signature of a nation.

- Strategy → a tool for startups, brands, and investors to signal identity.

For domain investors, ccTLDs are no longer optional. They are integral to a diversified portfolio, carrying both risk and extraordinary opportunity. For businesses, choosing a ccTLD can be as strategic as choosing a headquarters.

The future will bring new tensions between national control and global demand. But one truth is clear: in the digital age, every nation’s two-letter code is both a sovereign right and a strategic asset.