Modern economic commentary obsesses over speed. Faster execution, faster growth, faster exits, faster disruption. What almost no one asks anymore is a quieter, more revealing question:

Why do institutions no longer last?

Not why they fail — failure is visible.

But why their expected lifespan has collapsed so dramatically that collapse is now assumed rather than feared.

This is not a technological question.

Nor primarily a political one.

It is a civilizational signal.

Institutions — companies, brands, exchanges, banks, even cultural entities — are the scaffolding through which societies project continuity. When their lifespan shortens, something deeper is happening: memory is thinning, commitment is weakening, and capital itself is changing behavior.

This post examines that change through history, data, and structure — not ideology.

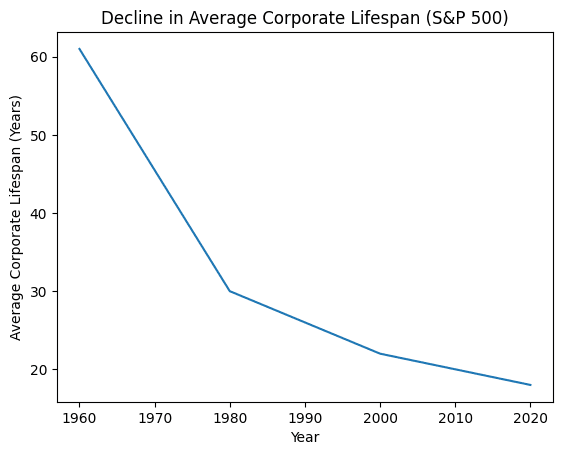

The First Signal: Lifespan Collapse

In the mid-20th century, to build a company was implicitly to build something meant to outlast its founders. Longevity was not a marketing slogan; it was assumed. Firms expected to survive wars, cycles, generational transitions.

That expectation is now gone.

The data is stark. In 1960, the average S&P 500 company expected to remain in the index for over six decades. Today, that expectation is under twenty years — and falling.

This is not merely because competition increased. Competition existed in 1900.

Nor because technology accelerated. Railroads, electrification, and industrialization were equally disruptive.

What changed is how institutions are formed, governed, and valued.

Institutions Used to Be Moral Objects

Before institutions were financial instruments, they were moral ones.

A bank was trusted because it survived panics.

A manufacturer mattered because it trained generations.

A name carried weight because it endured.

Longevity was not nostalgia — it was proof of alignment with reality.

In continental Europe especially, institutions were seen as custodians, not vehicles. They held memory. They accumulated reputation slowly. Their failure was rare precisely because dissolution meant social rupture.

Modern capitalism inverted this logic.

Institutions are now temporary containers for capital flows, optimized for velocity rather than endurance.

And capital responds accordingly.

Capital Has Learned Not to Trust Institutions

Here is the paradox:

While institutions are dying younger, capital is becoming more cautious, not less.

This appears contradictory until you realize capital no longer trusts permanence.

Instead of committing deeply to a few long-lived structures, capital fragments itself across:

• shorter cycles

• lighter commitments

• reversible exposures

This is why valuation has detached from durability.

Why brands are traded like options.

Why platforms replace firms.

Why “exit strategy” is discussed before purpose.

Capital no longer assumes tomorrow will resemble today.

That is not optimism.

It is strategic skepticism.

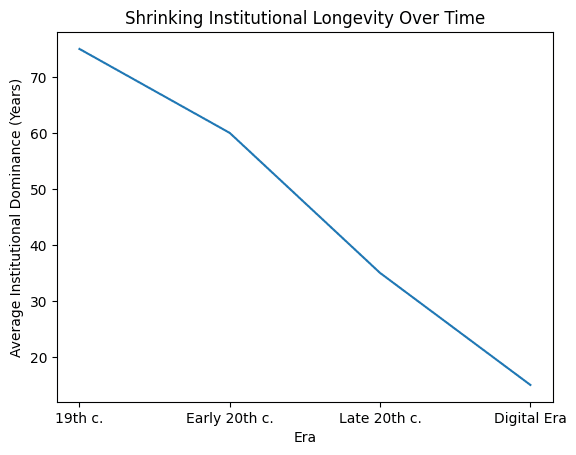

The Second Signal: Shrinking Dominance Windows

Historically, dominant institutions — not monopolies, but reference points — lasted generations.

In the 19th century, leading banks, shipping lines, manufacturers, and publishers often dominated for 70–100 years. They adapted slowly, but they adapted within identity.

By the digital era, dominance windows have collapsed to a decade or less.

This is not progress.

It is volatility masquerading as innovation.

Why This Matters More Than Quarterly Returns

Institutions do not merely produce goods or services. They produce time compression — the ability for individuals to trust that effort invested today will still matter tomorrow.

When institutions shorten their lifespan:

• training loses value

• loyalty becomes irrational

• craftsmanship disappears

• intergenerational transmission breaks

This is why young talent now optimizes for optionality rather than mastery. They are not lazy. They are rational actors in a system that no longer rewards depth.

Europe Understood This First — And Lost It

Continental Europe historically understood institutional time better than the Anglosphere.

Guilds, family banks, houses, and orders thought in centuries. Failure was dishonor. Continuity was duty.

But Europe dismantled its own structures under pressure from:

• post-war technocracy

• financialization

• regulatory homogenization

• cultural suspicion of authority

In doing so, it adopted Anglo-American capital logic without Anglo-American renewal capacity.

The result is a continent with memory but no mechanism to monetize it sustainably.

What Capital Is Quietly Seeking Again

Despite the noise, capital is not blind.

In recent years, you can observe a subtle reorientation toward:

• names with history

• assets with narrative continuity

• structures that resist commoditization

• domains where scarcity is linguistic, cultural, or symbolic

Not because they are fashionable — but because they survive cycles better.

Memory has become a hedge.

Not nostalgia — durability.

Why This Is Not a Reversion to the Past

This is not a call to recreate 19th-century institutions.

Those were hierarchical, exclusionary, and often unjust.

But they understood something we forgot:

An institution that cannot remember cannot be trusted with the future.

Modern systems optimized away memory because it slowed throughput.

Now throughput is high — and meaning is low.

Capital feels this tension before culture does.

The Coming Divide

The next decade will likely divide institutions into two classes:

- High-velocity, disposable entities optimized for extraction

- Low-velocity, memory-dense entities optimized for endurance

Most will choose the first path.

A minority will survive on the second.

Capital will increasingly discriminate between them.

Not loudly.

Quietly.

Patiently.

Final Thought

Every era believes it is more advanced than the last.

Few ask whether it is more durable.

Institutions dying younger is not a technical failure.

It is a philosophical one.

And capital — indifferent, unsentimental — is already adjusting.

Those who understand why will not need to be loud.

They will simply still be there.