There was a time when permanence was not a virtue to be defended. It was simply the default condition of life.

Capital stayed where it was placed. Businesses were built to outlast their founders. Property was acquired with the expectation that it would remain within a family for generations. Even failure, when it came, unfolded slowly enough to be understood. Time itself acted as a disciplining force. Decisions carried weight because they could not be easily undone.

That world is gone.

What replaced it did not arrive through a single revolution, nor through a conscious rejection of permanence. It arrived through a series of structural shifts—technical, regulatory, financial—that gradually made turnover not just possible, but desirable. Over time, speed became synonymous with intelligence, liquidity with health, and reversibility with safety. The ability to exit replaced the willingness to endure.

Today, we live in an economic environment designed not for holding, but for motion.

This article is not an argument against markets, nor against innovation. It is an examination of what is quietly lost when permanence ceases to be the organizing principle of capital—and what that loss does to judgment, responsibility, and ultimately value itself.

I. When Capital Was Expected to Stay

For most of modern economic history, ownership implied commitment.

Shares were bought with the intention of being held. Businesses were financed by people who expected to remain exposed to their consequences. Land ownership was inseparable from stewardship. Even public companies, for all their imperfections, were embedded in communities where reputation mattered and memory endured.

This was not a golden age. It was often inefficient, sometimes exclusionary, and frequently unjust. But it possessed one quality that modern systems struggle to replicate: time as a constraint.

When capital is expected to remain in place, errors compound slowly. Recklessness is punished by duration. Short-term gain cannot easily be separated from long-term cost. The investor who misjudges a business does not simply rotate out of the position; he must live with the consequences of his misjudgment.

This created a form of discipline that no regulation can easily substitute.

Boards thought differently. Owners behaved differently. Even speculators operated within a system that resisted constant churn. Markets moved, but they did not spin.

What mattered was not merely return, but continuity.

II. The Quiet Structural Break

The transformation did not occur overnight.

Between roughly the late 1960s and the early 1990s, a series of changes quietly rewired the architecture of markets:

- Commission deregulation

- Electronic trading

- Index construction and passive vehicles

- Financial derivatives

- The gradual rise of institutional asset management

None of these developments were, in isolation, destructive. Many increased access, lowered costs, and improved transparency. But together, they produced a profound unintended consequence: they detached ownership from time.

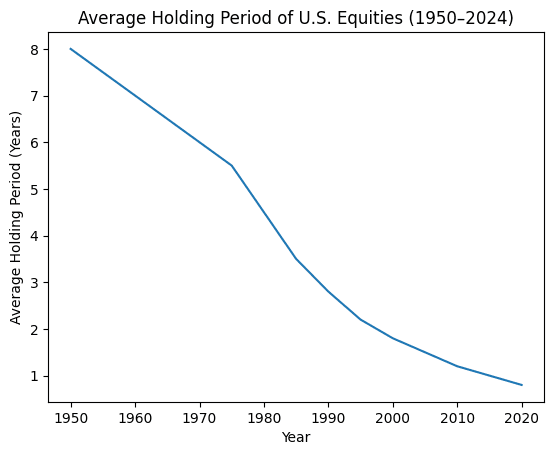

The first visible symptom of this detachment appears in one of the simplest metrics available: how long investors actually hold what they buy.

Source: NYSE Fact Books, World Federation of Exchanges, academic market structure research

The decline is unmistakable.

In the middle of the twentieth century, equities were typically held for seven to eight years. By the 1990s, that figure had already fallen below two years. Today, it is measured in months, not years.

This is not merely a behavioral change. It is structural.

When holding periods collapse, the meaning of ownership changes. Exposure becomes temporary. Conviction is replaced by optionality. Decisions are judged not by whether they are right, but by whether they can be reversed quickly.

Markets begin to reward agility over understanding.

III. From Ownership to Traffic

Once holding periods fall below a certain threshold, markets undergo a qualitative shift.

Capital ceases to behave like a stake and begins to behave like traffic. Assets are no longer held; they are passed through. Price discovery accelerates, but meaning evaporates. Valuation becomes a moving target, untethered from lived consequence.

This shift is often defended as efficiency. Liquidity, we are told, is unambiguously good. But liquidity is not free. It comes at the cost of commitment.

When everyone can leave at any moment, no one is truly responsible.

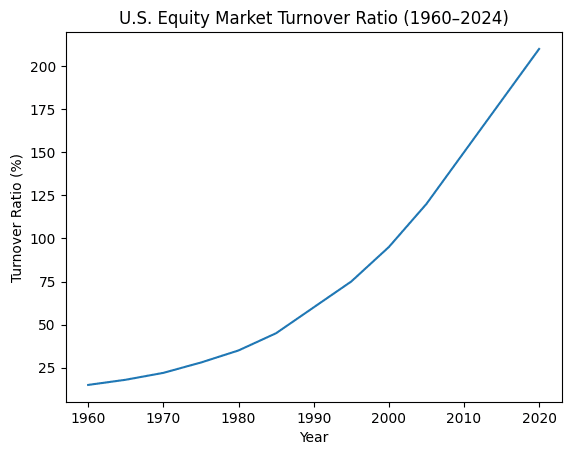

The second metric makes this even clearer: turnover.

Source: NYSE Fact Books, World Federation of Exchanges

A turnover ratio above 100% means that, in aggregate, the entire market changes hands more than once per year.

At that point, ownership becomes incidental.

This does not mean that markets stop functioning. They function remarkably well—if the goal is speed. But they function poorly if the goal is durability. Long-term signals are drowned out by short-term noise. Price becomes a reflection of flow rather than judgment.

The market begins to resemble a weather system rather than an institution.

IV. The Moral Dimension of Time

Time is not neutral.

When decisions must endure, they acquire moral weight. When they can be undone instantly, responsibility thins. This is not a philosophical abstraction; it is observable behavior.

Short-term systems encourage extraction over cultivation. They favor narratives that can be sold quickly over truths that require patience. They reward those who optimize for exit rather than those who commit to outcomes.

This is why permanence matters.

A system designed for turnover does not merely change how capital moves—it changes how people think. Judgment becomes tactical rather than reflective. Risk is reframed as volatility rather than consequence. Failure becomes a data point instead of a reckoning.

In such a system, even success becomes hollow. Gains are real, but fragile. Wealth accumulates, but trust erodes. Institutions persist, but legitimacy weakens.

V. Why This Matters Beyond Finance

The logic of turnover does not remain confined to markets.

It migrates outward.

Careers become sequences of short engagements. Communities lose continuity. Politics shifts from governance to performance. Culture becomes disposable. Even language accelerates, stripped of nuance in favor of immediacy.

When everything is reversible, nothing is sacred.

This is not nostalgia. It is diagnosis.

A civilization cannot be sustained on perpetual motion alone. Some things must be held long enough to matter. Some commitments must resist optimization. Some values must endure friction to retain meaning.

Markets are powerful tools. But when they are redesigned around speed rather than stewardship, they begin to shape society in their own image.

VI. The Illusion of Safety

Turnover is often defended as risk management.

If you can exit instantly, you are safe. If you can rebalance continuously, you are prudent. If you can hedge everything, you are sophisticated.

But safety purchased through perpetual exit is illusory.

True resilience does not come from constant motion. It comes from structures capable of absorbing stress without disintegrating. Permanence, properly understood, is not rigidity. It is the capacity to remain intact under pressure.

Systems built for turnover excel in calm conditions. They fail catastrophically under strain.

History bears this out repeatedly.

VII. What Permanence Requires

Permanence does not mean stagnation.

It requires:

- Time horizons long enough for consequences to unfold

- Owners who cannot easily escape outcomes

- Institutions that remember

- Capital that is patient enough to be shaped by reality

These conditions are increasingly rare—not because they are obsolete, but because they are incompatible with systems optimized for velocity.

Recovering permanence does not require abandoning modern finance. It requires reintroducing friction where it matters, and restraint where speed has outpaced wisdom.

This is not a call to return to the past. It is a call to recognize what was lost in the transition—and why its absence is now felt across domains that have nothing to do with markets.

VIII. The Question That Remains

We have built a world extraordinarily good at movement.

What we have not built is a world good at staying.

Permanence is not an aesthetic preference. It is a civilizational requirement. Without it, value becomes transient, responsibility diffuses, and meaning dissolves into throughput.

The question is no longer whether turnover can be increased. It clearly can.

The question is whether anything essential survives once permanence is no longer expected.

That question cannot be answered by graphs alone. But the graphs make one thing undeniable: the world we inhabit is not the one our institutions were designed for.

And until that mismatch is addressed, we will continue mistaking motion for progress—and liquidity for life.