For most of modern history, capital followed people.

Population growth meant labor.

Labor meant production.

Production meant investment.

Cities expanded, industries clustered, and states grew rich because people were there — working, consuming, reproducing. Demography was destiny. The map of capital and the map of population largely overlapped.

That alignment is breaking.

Across large parts of the developed world — and increasingly beyond it — people are leaving while capital remains. In some places, capital even concentrates more tightly as population thins. Entire regions hollow out socially while becoming wealthier financially, at least on paper. Property prices rise as schools close. Asset values climb as births collapse. The old logic no longer explains the new geography.

This is not a temporary distortion.

It is a structural shift.

To understand what is happening, we must abandon the assumption that capital still behaves as it did in the industrial and early post-industrial eras. The new map of economic gravity is shaped by forces that reward stability over vitality, ownership over participation, and systems over societies.

What follows is an attempt to describe that map — and the forces that are redrawing it.

The End of the Population–Capital Alignment

Until recently, capital needed people in a very literal sense.

Factories required workers.

Retail required foot traffic.

Infrastructure investment assumed long-term demographic growth.

States taxed labor to fund expansion.

Even financial capital, though abstract, depended on expanding populations to sustain demand, housing markets, pension systems, and public finance. Population decline was synonymous with economic decline. Regions that lost people lost relevance.

That assumption underpinned most economic policy well into the late twentieth century.

But over the past three decades, three quiet transformations began to sever this link.

First, capital became more mobile than labor.

Second, production became less dependent on local populations.

Third, ownership structures detached returns from local economic participation.

Individually, none of these was revolutionary. Together, they changed the gravitational field.

Capital no longer needs people in the same way. In many cases, it prefers not to have them at all.

Capital’s New Preferences: Stability, Predictability, Control

Capital does not think.

But it behaves.

And its behavior reveals preferences.

In the current era, capital increasingly seeks environments with the following characteristics:

- Strong legal systems

- Predictable regulation

- Low political volatility

- Reliable property rights

- Manageable labor pressure

- Minimal demographic turbulence

None of these requires a growing population.

In fact, declining or aging populations can be advantageous. They reduce labor militancy, dampen political disruption, and weaken redistributive demands. They stabilize consumption patterns. They make societies more conservative — not ideologically, but behaviorally.

From the perspective of capital, a shrinking society with intact institutions can be more attractive than a growing one with social volatility.

This is why capital increasingly decouples from demographic vitality.

The Rise of Asset-Dominant Economies

The second major shift is the rise of asset-dominant economic structures.

In asset-dominant systems, wealth accumulation depends less on producing goods or services and more on owning scarce assets:

- Real estate

- Financial instruments

- Intellectual property

- Infrastructure monopolies

- Regulated scarcity

These assets do not require local population growth to appreciate. In many cases, they benefit from scarcity — including human scarcity.

Housing markets provide a clear example. In numerous global cities, prices rise even as families disappear. Apartments become investment vehicles rather than dwellings. Ownership concentrates. Use declines.

Capital flows not to where people are forming lives, but to where assets can be stored, protected, and leveraged.

The result is a paradox:

places become richer as societies weaken.

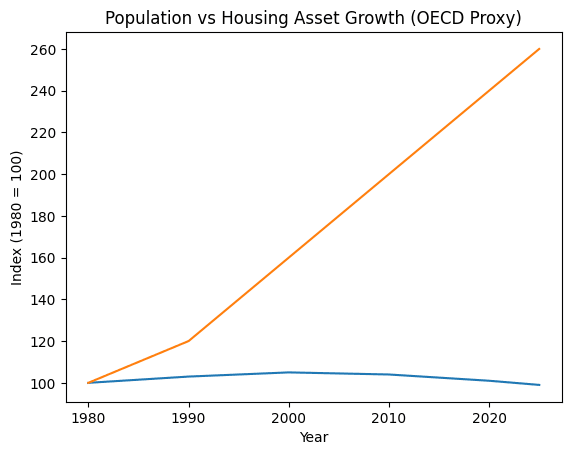

A comparison of long-term population trends with housing and financial asset appreciation across selected regions.

This graph would show that in multiple developed economies, especially in urban cores and select peripheral safe jurisdictions, asset prices have risen despite stagnant or declining populations.

The visual contradiction is the story.

Why People Leave — and Capital Doesn’t

People leave regions for familiar reasons:

- Lack of opportunity

- Declining services

- Aging demographics

- Cultural stagnation

- Weak future prospects

Capital evaluates different criteria:

- Legal continuity

- Asset liquidity

- Tax efficiency

- Political predictability

- Currency stability

These criteria often remain intact long after societies begin to fray.

Institutions outlive populations.

Legal systems outlast cultures.

Property registries persist when schools close.

Capital does not mourn the loss of civic life. It simply checks whether contracts are still enforceable.

As long as they are, it stays.

The New Centers of Gravity

Under the old model, economic gravity clustered where population density, production, and innovation overlapped.

Under the new model, gravity clusters where ownership structures intersect with institutional durability.

This produces several recognizable patterns:

- Capital islands inside declining states

- Urban cores detached from national demography

- Financial enclaves without social depth

- Peripheral regions serving as asset reservoirs

These are not thriving societies. They are functioning containers.

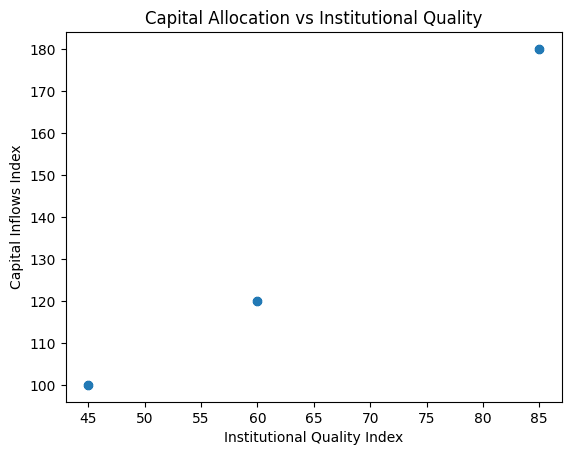

This graph would illustrate that capital aligns more closely with institutional reliability than with population growth.

The Illusion of Prosperity

From the outside, these regions often appear prosperous.

GDP per capita rises.

Asset values climb.

Public balance sheets stabilize.

But this prosperity is increasingly non-participatory.

It accrues to owners, not contributors.

It reflects valuation, not production.

It sustains systems, not communities.

The social consequences are visible:

- Declining birth rates

- Fragmented families

- Hollowed civic institutions

- Cultural thinning

Yet capital remains unimpressed. Its metrics are satisfied.

Why This Is Not Just “Late Capitalism”

It is tempting to frame this as a moral failure or ideological excess.

That is insufficient.

What we are witnessing is a phase change in economic structure — one driven by technology, financialization, and global legal harmonization.

Capital has learned to:

- Operate without labor growth

- Extract returns without local engagement

- Preserve value without societal renewal

This is not greed in the narrow sense. It is adaptation.

The tragedy is not that capital behaves this way — it always has.

The tragedy is that societies still assume it depends on them.

It no longer does.

The Silent Competition Between Regions

Regions are now competing on a new axis.

Not growth.

Not innovation.

Not even productivity.

They compete on capital survivability.

The winners are those that offer:

- Low institutional entropy

- Minimal political drama

- Durable property regimes

- Predictable decline

The losers are regions that attempt renewal without stability — or stability without ownership.

This explains why some areas with bleak demographic futures continue to attract capital, while younger, more dynamic regions struggle to retain it.

The Human Cost of Capital’s Detachment

When capital survives where people leave, the social contract fractures.

Citizens notice that:

- Work no longer leads to ownership

- Participation no longer leads to security

- Loyalty no longer leads to continuity

Trust erodes.

Withdrawal accelerates.

Exit becomes rational.

This feeds back into the system. As people disengage, capital becomes even more dominant, reinforcing the cycle.

What This Means Going Forward

The new map of economic gravity is not uniform. It is uneven, selective, and fragile in its own way.

Capital can survive without people — but only temporarily.

Institutions can persist without societies — but not indefinitely.

At some point, the container empties.

The question is not whether this model collapses, but where and how it fractures first.

Regions that mistake asset appreciation for vitality will be unprepared. Regions that recognize the distinction may yet adapt.

The Central Insight

Capital survives where people leave because it has learned to value order over life, structure over culture, predictability over possibility.

This is not sustainable in the long run.

But it is dominant now.

Understanding this shift — rather than denying it — is the first step toward navigating the century ahead.